Making Art, Part 2

I left art school with the question, “Am I a real artist?” along with its challenge: You are an artist only if you continue to create art beyond school.

I have made work. I left the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, returned to Western MA, got a job as a social worker, had a second child, and yes, I kept making art. I took classes at a local printmaking studio, framed the woodcuts, lithographs, and etchings, submitted them to shows, had a small first solo exhibit at a movie theater, then at a library. I worked at making art in an upstairs loft in the house we rented and then, when we moved to a house of our own, I worked in a small front room that seconded as a TV room and guest room.

When the kids were five, our family moved to Kyoto, Japan for a semester. Japan was a revelation, and I log that as the foundation of my seeing myself as a true artist. The drama of the landscape, the trees around our little rental in the northern outskirts of the town, it all demanded to be recorded. I took a bus to the city center, no easy matter considering that I couldn’t read a word on street signs, bus signs, nor understand anything anyone said, but I made it, found the art store, (this before cell phones and GPS), and stocked up on good paper and charcoal.

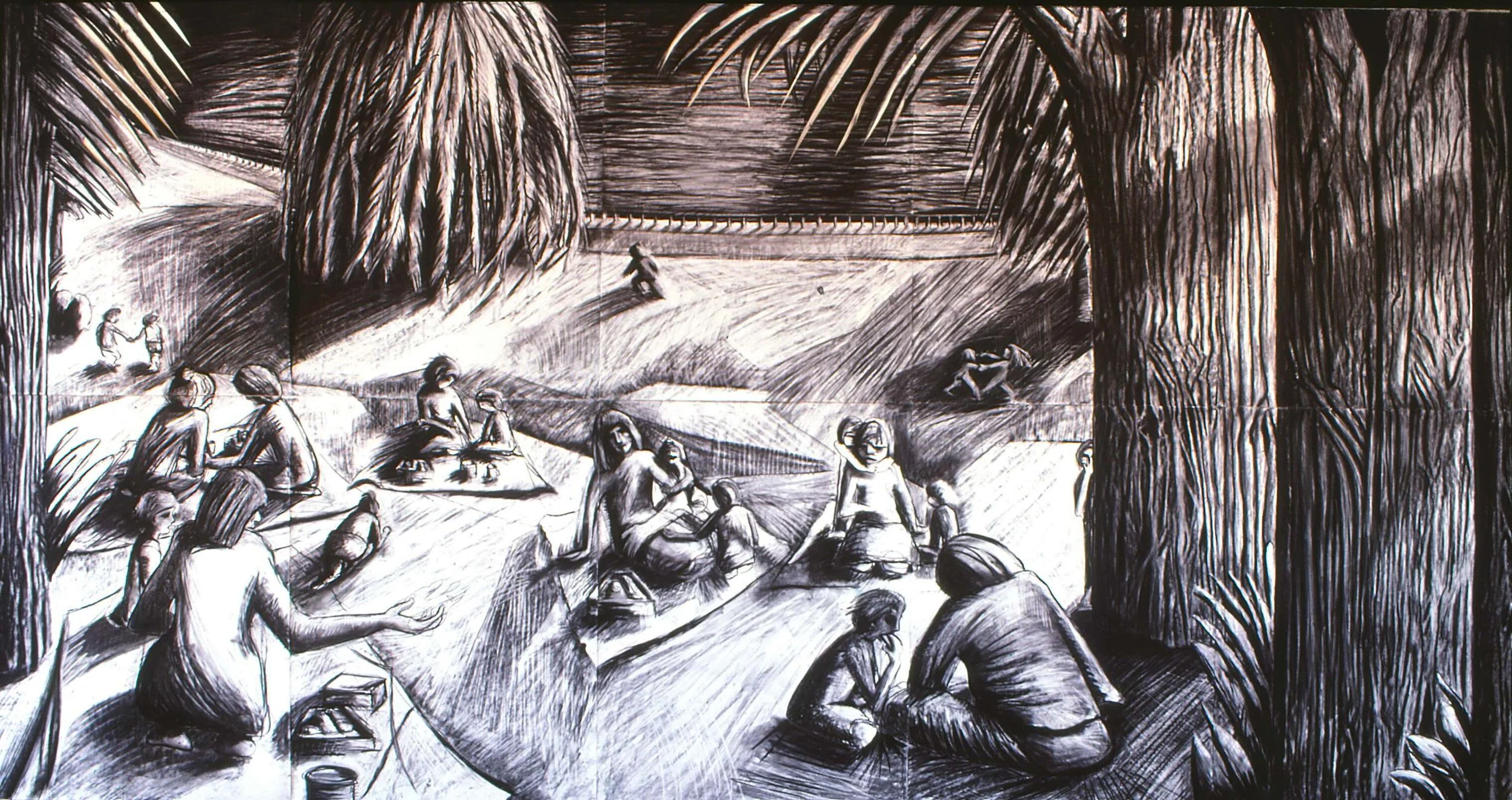

Kurama, Charcoal 80X60”

I returned to the little apartment and began drawing each day when the kids went off to their yochien, a little nursery school, for maybe two, two and a half hours before I had to pick them up for lunch. But it was enough. Enough to crate up and bring home ten to fifteen drawings of specific moments or places I’d seen. I combined two or four pieces of the white paper to expand the size of the drawings. ‘Kurama,’ four pieces, 80 X 60 inches, captured the awesome size of the redwoods in the forest north of our neighborhood.

‘Takaragaike,’ a massive drawing, 80 X 90 inches, showed my kids and others climbing jungle gyms in the huge park as I and the other nursery school moms sat on big blankets sharing food on an after-school outing. I did not depict the first day I arrived in Kyoto, exhausted with jet lag, when I brought my two sons and a neighbor’s kid to the big park, and my youngest, Mickey, within the first five minutes there, climbed to the top of the massive jungle gym and promptly, as if in a cartoon, plummeted down to the ground, hitting his head, bam, bam, bam, all the way down.

A disaster. I ran to his inert body, so small, five years of devilment, picked him up, called to the bigger neighbor boy and my older son and started frantically asking all the parents nearby in English about a hospital.

Takaragaike, Charcoal, 80X90”

“Where is a hospital?? Please! Please help me!” I was already running toward the street. No one understood me, and I couldn’t make out one word they said.

I ran, and ran, Mickey heavy in my arms, as I barked at the neighbor kid, asking if he knew a hospital nearby, which he didn’t. No cellphone meant running towards our new apartment and asking every passerby, “Hospital?” “Hospital!!!”

Hysterical. Distraught. Panicked.

He lived. I lived. The drawing of Takaragaike a remnant of that day, never shown, or maybe once. Packed away with the memories, along with ‘Akira’s Drowning,’ another large charcoal of an outing with an expat friend and his son to a river swim hole along with my husband. My husband and the friend so busy talking that when I looked up from the beach to check on my kids and the man’s younger son in the river, I caught sight of the toddler slipping under the water and catapulted to my feet, ran in and rescued him. The men missed the whole event.

River Passage Installation, Detail, Charcoal, Screens, Maché, Stones, 3000 sq. ft.

All the drawings that evolved from that semester trip and then the ensuing years of expanding dimensions gave birth to the massive charcoals I became known for, extending over studio walls, onto the ceiling, and into paper mâché sculptural trees. A world grown from a journey. A world of recognition that culture defines experience, that my ideas of being a woman were different than the ideas of my Japanese women friends, that my ideas about what matters were entirely different than the whole world I was enveloped by in Kyoto.

I sublet a studio upon return to the U.S. and then another larger one with a friend. A thousand square feet. All windows on one wall facing a canal and the hills of the Holyoke Range. Such light.

My drawings grew so large that they filled whole museum galleries including radiators and floors.

And the payoff? A site-specific installation exhibit in collaboration with my sculptor studio mate, Harriet Diamond, at the nearby art museum. Harriet made the paper maché sculptures of figures and rocks, and I created the drawn environment: all the walls and radiators and folding screens. First, I imagined the world, building a maquette in the shape of the specific gallery, and then finally created the images, one piece of expensive archival paper 50” X 38” after another covering all the surfaces bumper to bumper. I started the drawing about the river near my house with a deep perspective view of trees lined up towards the horizon, and a peek at water beyond. I used six sheets of paper to create the big charcoal drawing, 100” X 114”, and then, stepping back day after day, squinting my eyes almost shut, I realized that another two pieces of paper on the left side would help rebalance the drawing, skew it off its symmetrical predictability. I tacked the new white paper on the wall and then found myself adding two more. The piece shifted from a statement about perspective to a forest scene where the viewer entered a meandering walkway along a river path.

Running by the River, Detail, Charcoal, Paint, Cardboard Tubes, Maché, 2000 sq. ft.

It was when I added my own sculptural trees that I moved from large scale drawings to full installation mode.

What I didn’t yet know was that I could and would build whole environments. At first the worlds were simple comments on the familiar but Buddhist-like landscape of New England. What made it Buddhist? Maybe the lack of grandeur or uniqueness — the woods I had become so connected to — all those dog walks and kid walks and walks with friends, a half block down my street and onto the river path — those woods offered a warm blanket of safety. And the river, the Mill River, flowing, flowing… where I rafted with my kids during the summer, ice skated when it was freezing, and skied down when it snowed — that small but comforting river meant home.

Did I identify as an artist all those years of drawing, constructing, buying the largest size Sono tubes to create trees, then adding mammoth cardboard tubes from the textile mill machines below my studio in that old mill building in Holyoke? I’d attach one tube on top of another vertically and paste paper mâché shaped cardboard boxes to the tubes for protrusions, paint it all white, then draw with charcoal on the lines, bulges and hollows of the tree forms, finally creating full corner vignettes, even adding rocks of mâché. And don’t get me started on the installation process of creating the environments within the venues —trucks, ladders, drills, hammers, up and down, up and down. So, did I finally comprehend that it looked like I was an artist?

No. I still said, “I make art,” when asked what and who I was. Other friends called themselves artists, but I knew that wasn’t me. I was a social worker, a therapist, a mom, a daughter, a wife, then a divorced woman, who made art…. (To be continued!)